I have arrived at the conclusion that record collectors don’t actually like music. If anything, they positively hate it.

Speak to any record collector and they will slaver over the virtues of a sixty-year-old L.P. in a proper, thick reinforced cardboard sleeve with thick grooves. Ask their views about the music contained on that L.P. and they fumble and bluff. They would never dare do something as base and vulgar as listen to the music. It would mar the L.P.’s market value, strip the record of its virginity.

Instead they solemnly arrange their L.P.s – never anything as crass or impure as compact discs, never mind cassettes – on shelves, in careful alphabetical and chronological order, with nary a thought save the monetary treasure trove that they hopefully represent. Not for them a blissful slumber or the cosy company of their partner at four on a Saturday morning; they are already out in their cars or vans, heading for the car boot sales to systematically strip them of everything worth buying. Some will immediately trade them on the open market, while others are in many cases benighted record shop owners, slowly being squashed by the internet (and the squashing is not necessarily the internet’s fault), looking to beef up their stock.

You will hear them perorate endlessly about audio quality, crispness, fullness and so on forevermore, and little about how the music on those records moves or affects them, if it ever did. They actively despise the music for getting in the way of the record’s potential value. A perfect record for them would be The Wit And Wisdom Of Ronald Reagan (1980) which is entirely blank on both sides.

Far, far worse is the fact that their cornering of the market cordons off so much potentially great music from ears which might be considerably more receptive. The endless limited edition treadmill is enough to turn people off buying records at all – which no doubt is the collectors’ intention. This inevitably means that music that could change people’s lives remains sealed off and unheard, and consequently changes nothing.

These puritan collectors – if taken to their logical extreme, puritans are what they be; as with the Khmer Rouge, they’d be eager to ban music altogether or confine it to joyless, sexless yea-worshipping traditional authenticity – throw their hairy hands up in horror when confronted with deceased entertainers from a different (and better) age, such as John Lennon or Steve McQueen, photographed listening to music with all their records in a disorganised heap. How dare they, yell those puritans at artists who achieved more in their brief lives with more talent than they themselves can ever hope to have – have they no respect for records?

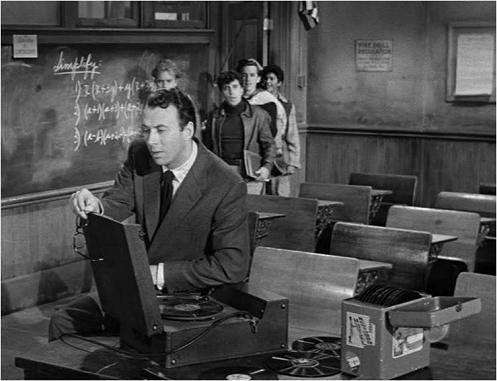

Well, no, because respect for records was what your parents did – and I look at some record collectors and feel extremely relieved that they are not my husband or father – or what Joshua Edwards does with his ancient jazz 78s in Blackboard Jungle (of course, we know that was only a plot device; if you really did spend fifteen years painstakingly assembling a collection of hard-to-find 78s, would you run the extreme risk of playing them to a bunch of unruly kids, even ones played by actors in their twenties? These days you’d just activate Spotify on the laptop and there wouldn’t be any problem locating Frank Sinatra or Joni James tunes. In any case, “Jazz Me Blues,” which was a euphemism for “fuck me,” is a far more sexually potent record than even “Rock Around The Clock”). Whereas the whole point of the rock ‘n’ roll (not “rock and roll,” just as “drum n’ bass” was never going to be “jungle”) thing was to eject that respect right out of the window.

Pop music is, as many of its finest practitioners did and in some cases still do tell you, disposable in nature. You grooved and did all sorts of natural and outrageous things to a bunch of records for maybe three months, then got rid of them in favour of a new bunch. That was how it worked and everybody was happy. There wasn’t the time, space or will to look back. In 1967, radio’s idea of an oldie was to play something from 1965. There was no backlog of “stuff” to deal with, no “legacy,” because this wasn’t classical, folk or jazz music.

But now there are seventy or so years of “stuff,” of accumulated history, with which to reckon, and our reckoning warps that history until it is unrecognisable. Hence the scrupulous, or if you prefer (and I certainly do) unscrupulous remixing and remastering of old pop records specifically mixed to sound good on the technology most readily available at the time, namely transistor radios or tinny Dansette players with one speaker. Hence the Beatles’ music being ruined forever by their producer’s son, tinkered and messed about with to make it digestible to the scared ears of today. Rather than admit that the original Beatles records largely made brilliant use of, by today’s standards, severely limited studio technology, they want them remade by today’s standards, thus robbing them of all their charm, originality and spike.

Quite often, we don’t want to know who did or played what and where or why. We nostalgically consider L.P. covers as they were, with a portrait of the artist on the front and a track listing and composer/producer credits – and occasionally a breathlessly brief sleeve note – on the rear. There was no history or contextualisation. You had to work everything else out for and by yourself. In his sleeve note to the original British ten-inch edition of the first Elvis Presley album, Bob Dawbarn went out of his way to make the music sound palatable to jazz fans, comparing Presley to Billie Holiday. The teenagers who largely bought that album and sent it to number one completely ignored the notes, and the jazz fans hated Elvis anyway, so what was the point?

That accumulated history drags upon our backs and helps to suffocate the future. So much record collecting has become not about assembling a library of music that one actually loves, but a furtive and frantic need to “own” everything, to have all the “essential” records (essential to whom, and for what? Records are not food, air or water) in as pristine and “pure” (subtext: virginal) a form as possible.

Even those collectors who profess or pretend to keep up with new developments act like junkies, so blinded by their self-imposed mission to “complete” their collection that they fail to see that the habit robs them of homes, careers, relationships and a future. This alleged completeness is not driven by any great will within the collectors other than a desperation not to be left out. They slavishly purchase new records which receive warm reviews in the media, failing to comprehend that music critics act only in obeisance to fashion, and praise that which they feel is the most fashionable music of any given time because that might keep them in work. Then they sit about for months, glumly waiting to “get it” and wondering why they can’t.

History has proved repeatedly that most records now universally acclaimed as “classics” were at the time of their release met with blankly confused incomprehension or dismissed with a fashionable sneer. Hence brightly-coloured entitled trash like West End Girl or LUX is praised because it’s considered fashionable to do so, whereas The New Sound largely generated “help Mummy, I don’t understand, he’s too clever for his own good” how-dare-plebs-show-us-up-subtextual whimpering. But the collectors usually tend to miss or skip the jewels and pick up the trendy minnows instead.

I can’t do any of that any more, even if I wanted to, because pop music is also essentially for teenagers and you’re supposed to grow out of it. I came to pop the other way round from most people in that I started with jazz and classical, then expanded my musical horizon. I think I understand pop better from that particular perspective as a result.

But I’m also in my sixties, a time when professing continued interest in modern pop music becomes distinctly creepy. Hence I’m marooned between two poles. The people with whom I grew up or worked in the past have, I suspect, largely stayed there as far as their musical tastes are concerned. Not that I’ve ever been invited to a school or old workplace reunion – not that I would accept any such invitations, since I’m not the same person now that I was then, or am perhaps too much the same person (it’s hard to tell at times) – but I think it safe to assume that my former peers would prove adherent to the music they loved forty or fifty years ago, when they were young and life had yet to happen to them, rather than having Moved On.

Extend that premise to, say, social media, and it’s identical; everywhere I see people reminiscing about something from the eighties or nineties – and it is ALWAYS white guitar-based indie music – rather than enthuse about something that came out last week. But talk about music of today and at best I am in receipt of metaphorical piteous stares. I can’t discuss it with those young enough to be my grandchildren. As I have never had any children – a combination of circumstances and choice - I can’t discuss it with them either.

I don’t really go into record shops any more. Bookshops, yes; record shops, not nearly as much. In my current state of health I find browsing in record shops awkward and painful – there’s never anywhere in HMV or Fopp to sit, and while Rough Trade East does have seats at its entrance, it’s too far out of my way to get to, is populated by smug hipster creeps, doesn’t take cash and sells the only copy they ordered of anything I like to Gareth Collect at 9:31 on the Friday morning that it comes out.

In addition, record shops – see also that saddest of arenas, record fairs – now resemble grim, grey morgues, with unaffordable and unattractive L.P.s in serrated ranks like an MI5 filing cabinet. When I was young, record shops were colourful, exciting and of the moment. Now they’re like museum photographs of record shops.

In any event, there’s no way I could venture into a record shop now and purchase anything by the latest pop sensation without provoking a lot of suspicious glances; what’s that old creep with the stick doing buying THAT’S SHOWBIZ, BABY!? Oh no, we order all of our CDs online now and just wait for them to come through the letterbox. It’s like Christmas every day with all those packages!

But we don’t “collect”; we listen to what we get and aren’t too fussy about its continued upkeep. We do have a sort of order in terms of where we put things but it isn’t a church. Moreover, streaming, for all its self-administered woes, actually defuses any urge to collect music; if there are a lot of new records out each Friday we just stick them on the streaming, listen to them and, if we like them sufficiently to want to listen to them without being interrupted by ads, buy them. We can’t buy everything because we’re not Elton John and there’s a limit to how many records most people can afford to buy (I do wonder, however, about the middle-aged bloke one occasionally sees in second-hand record shops in the middle of the weekday, busily buying up stuff – I’m on holiday, mate, but how can you afford to buy all of that; shouldn’t you be working in the middle of the day? I have my theories about how these people make a living, but…).

Nevertheless, we love music, Lena and I, and love it enough to want to try and keep it out of the grasping hands of those who would silence it for the sake of a quick and easy profit because that really isn’t what music – of any kind – ought to be about. Consider how Joshua Edwards bought 78s as opposed to painfully-annotated boxed sets, and was happy to nod his head to Stan Kenton on the bar’s jukebox. While a fool for the sake of plot convenience, he was still the type of record collector which has most likely long since headed the way of the dodo.